Capacitors don’t last forever – an unfortunate fact of life for those who collect vintage electronics. The common electrolytic capacitor is one of the most problematic. It’s the type that looks like a little metal can, and after a couple of decades electrolytics tend to start leaking corrosive capacitor goo onto the PCB. You may recognize the strange smell of fish as an early warning sign. Eventually the goo will destroy traces on the PCB, or the changing electrical properties of the capacitor will cause the circuit to stop working. If you want to preserve your vintage equipment, that’s when it’s time for a “recap”.

I have an old Macintosh IIsi computer that dates from around 1991. A few years ago it started acting funny and having trouble turning on, so I sent the logic board to Charles Phillips’ MacCaps Repair Service. He did a great job with the capacitor replacement, and the machine was working great again. But then a few months ago it started to develop new problems that pointed to the need for a power supply recap. I could rarely get it to turn on at all, and when it did, I couldn’t get it to turn off again without unplugging it. Simply plugging the computer into wall power without turning it on caused strange clicking noises from the PSU. And oh, that fish smell.

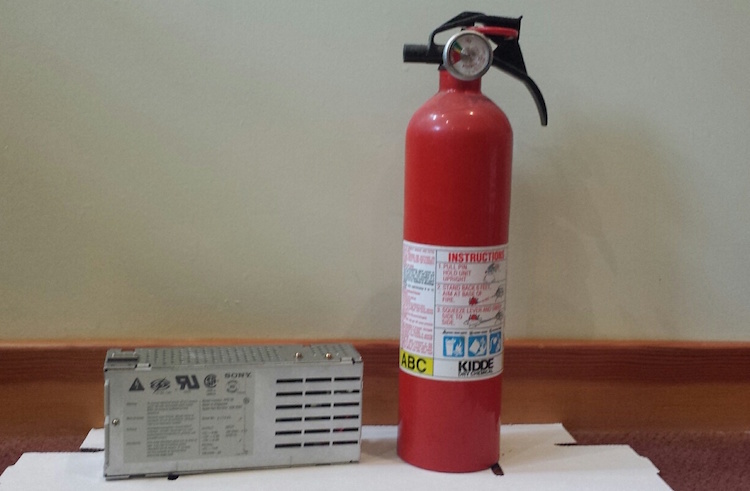

I was going to send the PSU off for a recap. After all, there’s a big warning printed right on the metal cover saying danger, do not open, no user-serviceable parts inside. And while there’s not much danger in a 5 volt logic board, there is a potential for real danger in a power supply drawing 5 amps at 110 volts AC. But then I thought no, I should really get comfortable doing this kind of work myself. I have the tools and the skills, just not the experience or confidence. What’s the worst that could happen? OK, it could blow up and catch fire, but I’ve got a fire extinguisher.

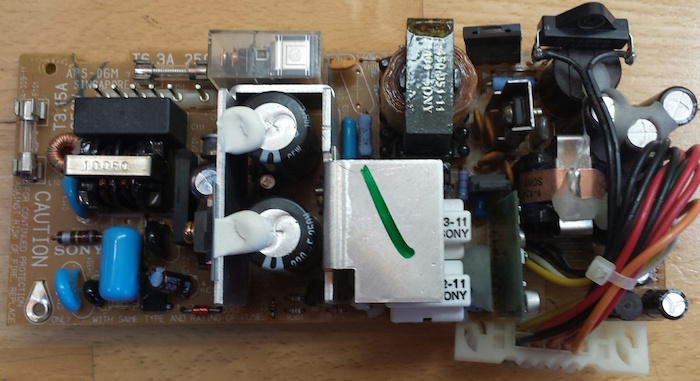

There are 12 electrolytic capacitors in this power supply, whose types and values are listed here. Two of these are surface mount caps on a daughterboard that’s connected to the main PCB, and the others are all through-hole caps. Because I’m both timid and lazy, I really did not want to replace 12 caps. After reading this discussion thread from someone who did a similar repair, I decided to replace only the three capacitors that seemed most likely to be causing the problem. Two of these were the SMD caps on the daughterboard, which apparently are involved in some kind of PWM control circuit. The third was a 400V cap in the AC section of the power supply. It’s located directly next to some big heat sink thing, and has probably been slowly baking for 25 years.

To help with the job, I bought a cheapo vacuum desoldering iron. This makes desoldering of through-hole components easy. Just put the iron over the pin, hold for a second, then press the button to release the plunger and mostly all the solder is sucked up. I used this to desolder the daughterboard too. I had to revisit a few pins to get them totally clean, but overall the process was simple. I don’t do enough desoldering to justify the cost of a fancier desoldering gun with a continuous suction vacuum pump, so this seemed like a good tool for occasional use.

I removed the two SMD capacitors on the daughterboard with a hot air tool. I’m not sure how you would do that without such a tool – just rip them off with pliers? The hot air worked fine, except when I used tweezers to slide off the caps after the solder had melted, I accidentally pushed one of them right through a bunch of other little SMD components, whose solder had also melted, and ended up with a jumbled heap of little components half soldered together in a corner of the board. Ack!!

Here’s the daughterboard, before I wrecked it. The four components at bottom right were all pushed into a pile in the corner. A couple of them actually fell off the board, as did one of the pins. But with some patience I was able to separate them all and get things cleaned up, and I think I even put everything back where it was originally.  After removing the old caps, I cleaned up the board with isopropyl alcohol and a toothbrush to remove the capacitor goo.

After removing the old caps, I cleaned up the board with isopropyl alcohol and a toothbrush to remove the capacitor goo.

The last step was soldering in new capacitors, and putting it all back together. Compared to everything else, that was a breeze.

When the time came for testing, I didn’t take any chances. I brought the whole machine outside, with a fire extinguisher in hand, ready for anything! I plugged it in, pressed the power switch, and… WOOHOO! It booted right up, and everything now looks a-ok. I can boot from the rear power switch or the keyboard power button, and the soft power-off function works again too. I feel like Superman!

This was my first time recapping anything, and I won’t be so timid about recapping next time the need arises. The whole process took about three hours, including lots of futzing around during disassembly and reassembly. If I hadn’t blundered by knocking off a bunch of unrelated SMD parts, I probably could have done the whole job in about an hour.